الثورة الزراعية العربية

ناعورة في مدينة حماة السورية

|

عام |

|---|

|

تاريخ |

|

أنواع |

|

تصانيف |

|

'الثورة الزراعية العربية[1] (المعروفة أيضًا باسم الثورة الخضراء في القروسطية،[2][3] والثورة الزراعية الإسلامية '[4] والثورة الخضراء الإسلامية)[5] هو مصطلح ابتدعه المؤرخ أندرو واطسون في بحثه لعام 1974 حول التحول الجذري في الـزراعة بين القرنين الثامن و الثالث عشر في بلاد المسلمين.[1] كان هذا امتدادًا لفرضية سابقة حول الثورة الزراعية في إسبانيا الإسلامية تم اقتراحها قبل ذلك بكثير في عام 1876 من قبل المؤرخ الإسباني أنطونيا غارسيا ماسيرا.[6]

يقول واتسون أن الاقتصاد الذي أقامه التجار الـعرب وغيرهم من التجار المسلمين في جميع أنحاء العالم القديم مكّن من انتشار العديد من المحاصيل والتقنيات الزراعية بين أجزاء مختلفة من العالم الإسلامي، وكذلك تكيف المحاصيل والتقنيات من وإلى المناطق الموجودة خارج العالم الإسلامي. وتم توزيع محاصيل من إفريقيا مثل سورغم ومحاصيل من الصين مثل الـحمضيات والعديد من المحاصيل من الهند مثل الـمانجو والأرز والقطن وقصب السكر، في جميع أنحاء الأراضي الإسلامية، والتي لم تكن تزرع هذه المحاصيل من قبل، وفقًا لواتسون.[1] كما أورد واتسون ثمانية عشر محصولاً من هذه المحاصيل التي تم نشرها خلال الفترة الإسلامية.[7] ويقول واتسون أن هذه المقدمات مع زيادة الـميكنة الزراعية، أدى إلى تغييرات كبيرة في الاقتصاد والتوزيع السكاني والغطاء النباتي[8] والإنتاج الزراعي والدخل ومستويات السكان والتمدد الحضري وتوزيع القوة العاملة والصناعات المرتبطة والطبخ والنظام الغذائي والملابس في العالم الإسلامي.[1]

وبغض النظر عن التعليقات المعاصر الهامة عن فرضية واتسون،[9][10] تتحدى دراسة حديثة أجراها مايكل ديكر (2009) فكرة الثورة الإسلامية.[11] فبالاعتماد على الأدلة الأدبية والأثرية، يبين ديكر أنه على عكس فرضية واتسون الرئيسية، كان انتشار الزراعة على نطاق واسع واستهلاك المواد الغذائية الأساسية مثل القمح الصلب والأرز الآسيوي[؟]والسورغم والقطن أمرًا شائعًا بالفعل في عهد الإمبراطورية الرومانية والإمبراطورية الساسانية، قبل قرون عديدة من الفترة الإسلامية. وفي الوقت نفسه، يقول أن دورها الفعلي في الزراعة الإسلامية تمت المبالغة فيه، ويخلص ديكر إلى أن الممارسات الزراعية للمزارعين المسلمين لم تختلف جوهريًا عن تلك الخاصة بعصور ما قبل الإسلام، ولكنها تطورت من الخبرة الهيدروليكية و"سلة" النباتات الزراعية الموروثة عن أسلافهم الرومان والفرس.[12]

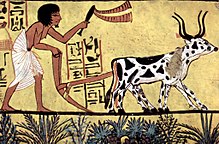

كما يشير ديكر إلى الحالة المتطورة لأساليب الري القديمة التي "ترد على أجزاء كبيرة من فرضية واتسون."[13] وهذا يوضح بشكل أساسي أن جميع الأجهزة الزراعية الهامة، وتشمل الطواحين المائية الهامة (انظر قائمة بالطواحين المائية القديمة) وأيضًا النواعير والشادوف ونواعير حماة والساقية[؟] والطنبور وأنواعًا[؟] مختلفة من مضخات المياه، كانت معروفة على نطاق واسع ويتم استخدامها من قبل المزارعين اليونانيين والرومان قبل فترة طويلة من الفتوحات الإسلامية.[14][15][16][17]

وقد جادل أشتور أن الإنتاج الزراعي، خلافًا لفرضية واتسون، انخفض في مناطق كانت تحت الحكم الإسلامي في العصور الوسطى، بما فيها مناطق في العراق (بلاد ما بين النهرين) ومصر, وذلك بناء على سجلات الضرائب المحصلة على المساحات المزروعة.[18]

المراجع

↑ أبتث Watson، Andrew M (1974)، "The Arab Agricultural Revolution and Its Diffusion, 700–1100"، The Journal of Economic History، 34 (1): 8–35، doi:10.1017/S0022050700079602 .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}.

^ Watson، Andrew M (1981)، "A Medieval Green Revolution: New Crops and Farming Techniques in the Early Islamic World"، The Islamic Middle East, 700–1900: Studies in Economic and Social History .

^ Glick، Thomas F (1977)، "Noria Pots in Spain"، Technology and Culture، 18 (4): 644–50، doi:10.2307/3103590 .

^ Decker 2009, pp. 187–206.

^ Burke، Edmund (June 2009)، "Islam at the Center: Technological Complexes and the Roots of Modernity"، Journal of World History، University of Hawaii Press، 20 (2): 165–86 [174]، doi:10.1353/jwh.0.0045

^ Ruggles، D Fairchild (2003)، "Botany and the Agricultural Revolution"، Gardens, landscape, and vision in the palaces of Islamic Spain، Penn State University Press، صفحات 15–34 [31]، ISBN 0-271-02247-7

^ Decker 2009, pp. 187–8: "In support of his thesis, Watson charted the advance of seventeen food crops and one fiber crop that became important over a large area of the Mediterranean world during the first four centuries of Islamic rule (roughly the seventh through eleventh centuries C.E.)”

^ Watson، Andrew M (1983)، Agricultural Innovation in the Early Islamic World، Cambridge University Press، ISBN 0-521-24711-X .

^ Johns، J (1984)، "A Green Revolution?"، Journal of African History، 25 (3): 343–4، doi:10.1017/S0021853700028218 .

^ Cahen، C؛ Watson، Andrew M. (1986)، "Review of Agricultural Innovation in the Early Islamic World, by Andrew Watson"، Journal of the Social and Economic History of the Orient، 29 (2): 217، doi:10.2307/3631792 .

^ Decker 2009, p. 191: "Nothing has been written, however that attacks the central pillar of Watson's thesis, namely the "basket" of plants that is inextricably linked to all other elements of his analysis. This work will therefore assess the place and importance of four crops of the "Islamic Agricultural Revolution" for which there is considerable pre-Islamic evidence in the Mediterranean world."

^ Decker 2009, p. 187.

^ Decker 2009, p. 190.

^ Oleson 2000, pp. 183–216.

^ Oleson 2000, pp. 217–302.

^ Wikander 2000, pp. 371−400.

^ Wikander 2000, pp. 401–2.

^ Ashtor، E (1976)، A Social and Economic History of the Near East in the Middle Ages، Berkeley: University of California Press، صفحات 58–63 .

المصادر

Decker، Michael (2009)، "Plants and Progress: Rethinking the Islamic Agricultural Revolution"، Journal of World History، 20 (2): 187–206، doi:10.1353/jwh.0.0058 .

Oleson، John Peter (2000)، "Irrigation"، in Wikander، Örjan، Handbook of Ancient Water Technology، Technology and Change in History، 2، Leiden: Brill، صفحات 183–216، ISBN 90-04-11123-9 .

Oleson، John Peter (2000)، "Water-Lifting"، in Wikander، Örjan، Handbook of Ancient Water Technology، Technology and Change in History، 2، Leiden: Brill، صفحات 217–302، ISBN 90-04-11123-9 .

Wikander، Örjan (2000)، "The Water-Mill"، in Wikander، Örjan، Handbook of Ancient Water Technology، Technology and Change in History، 2، Leiden: Brill، صفحات 371–400، ISBN 90-04-11123-9

Wikander، Örjan (2000)، "Industrial Applications of Water-Power"، in Wikander، Örjan، Handbook of Ancient Water Technology، Technology and Change in History، 2، Leiden: Brill، صفحات 401–412، ISBN 90-04-11123-9

وصلات خارجية

Introduction، The Filāḥa Texts Project .

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

بوابة تقنية

بوابة زراعة